Início » english

Category Archives: english

New Mexico scientist builds carbon dating machine that does not damage artifacts

Via / T. S. Last / Journal Staff Writer

Scientists at the New Mexico Office of Archaeological Studies use a Low Energy Plasma Radiocarbon Sampling device on a sample of gelatin at its lab near Santa Fe. The machine is used to date artifacts by doing minimal damage to the sample. (Eddie Moore/Albuquerque Journal)

The contraption he built looks a little like something you might see from “The Nutty Professor.”

But Marvin Rowe is no nut. That machine he built, and what it’s used for, helped Rowe win the prestigious Fryxell Award for Interdisciplinary Research from the Society of American Archeology two years ago.

Marvin Rowe, a scientist at the New Mexico Office of Archaeological Studies, adjusts the Low Energy Plasma Radiocarbon Sampling device he built to date artifacts with minimal damage. (Eddie Moore/Albuquerque Journal)

“We call the process Low Energy Plasma Radiocarbon Sampling,” said New Mexico’s state archeologist Eric Blinman, who credits Rowe with inventing the process. “But a lot of people just refer to this as ‘Marvin’s Machine.’”

The process is important because, unlike other methods of radiocarbon dating that destroy the sample being tested, LEPRS preserves it. It also works on tiny samples – even a flake of ink or paint – and is considered a more accurate means of dating.

“With standard radiocarbon dating, there’s a risk of contamination of carbonates. They have to use acids and, within that process, you lose a large part of your sample and you destroy it,” Blinman explained. “But we now have the ability to date incredibly small amounts of carbon – 40-100 millionths of a gram – and that is the real revolutionary aspect of this. And the ancillary part of that is it’s non-destructive.”

That’s important to Nancy Akins, a research associate with the Office of Archaeological Studies, who in February was having a bison tooth and sheep bone tested by “Marvin’s Machine.” The items were excavated from the site of a rock shelter in Coyote Canyon north of Mora.

“It could be 500 years old or it could be 5,000 years old,” she said of the bison tooth, the result allowing her to complete her report of the site that she’s determined to have been used by humans as a hunting outpost starting 1,700 years ago.

“I’m just waiting on the dates, because it’ll change everything if we get dates where I can actually say, ‘OK, that’s what the sheep bones date to and that’s what the bison dates to.’ It tells us an awful lot about how they were using the land on the east side of the Sangre de Cristos.”

Because a lot of that part of New Mexico is private property or under land grants, such finds as the one in Coyote Canyon are rare, she said.

“Unless there’s a road or something, we don’t have any information at all. This is one of the very, very few sites in Mora County that have been excavated,” she said of the site reported by the state Department of Transportation.

And when she gets her answers and completes her report, she’ll still have the bison tooth and sheep bone.

A buffalo tooth rests in a tube of the Low Energy Plasma Radiocarbon Sampling machine located in the New Mexico Office of Archaeological Studies lab. The tooth was found at a site near Coyote Creek north of Mora. The machine is used to date artifacts without damaging to the sample. (Eddie Moore/Albuquerque Journal)

One of a kind

Rowe won his Fryxell Award “based in his prominent role in developing methods for rock art dating and minimally-destructive dating of fragile organic artifacts,” as well as his scientific analysis, scholarship and student training, according to the SAA website.

The achievement has been decades in the making. Rowe and two colleagues at Texas A&M’s Department of Chemistry built the first plasma dating machine in 1990 while exploring ways to extract organic carbon from pictograph samples.

“Other people have been successful dating charcoal paintings,” Rowe explained. “But, in the United States at least, most of the paintings are not charcoal. Most of them that I’ve encountered are inorganic pigments and that’s where the importance of the small sample comes in.”

Blinman adds that, under the best of circumstances, standard radiocarbon dating requires 30 milligrams of carbon. Rock art pigments don’t have that much carbon in them. But “Marvin’s Machine” can date material 100 millionths of a gram or less.

Blinman said the process’s capability to date very small samples would allow, for instance, determination of the age of the ink on a Chinese text written on bamboo. “The people who will fake texts can get their hands on old bamboo,” he said. Normal carbon-dating can’t date the ink because it requires too large a sample. “We can flake off a piece” and date it, Blinman said. “If the ink is old, then it’s real.”

Rowe is probably the world’s foremost authority on radiocarbon rock art dating. He says much of what he learned was by trial and error. In fact, the first machine he and his Texas A&M colleagues built caught fire and was destroyed.

Currently, there are only three LEPRS machines in existence – one in Michigan and one in Arkansas, both procured by former students of Rowe – but the one at the lab located at the New Mexico Office of Archeological Studies off N.M. 599 in south Santa Fe is the most sophisticated.

“Marvin has learned so much from the previous two (machines) about their construction and their use that when we offered him space and the opportunity to build one here, it was sort of like he was able to do all the things he sort of wanted to do, but couldn’t under the circumstances of the research at Texas A&M,” said Blinman.

Using plasma to scrub artifacts

Traditional carbon dating estimates age based on content of carbon-14 (C-14), a naturally occurring, radioactive form of carbon, and requires destruction of an object. A piece of an organic object – a bone fragment or weaving, for example – is washed with acid at high temperature to remove impurities and then burned in a chamber.

The carbon dioxide gas produced is run through an accelerator mass spectrometer, which measures the decay of radioactive carbon 14 – the more the carbon 14 has decayed, the older the object is. Comparisons are also made with the amounts of C-14 expected to have existed in the atmosphere in the past.

Blinman explained that Rowe’s alternative process is based on plasmas – ionized gas made up of groups of positively and negatively charged particles, and one of the four fundamental states of matter, alongside solid, liquid and gas. Plasmas are used in television displays and in florescent lights, which use electricity to excite gas and create glowing plasma.

In Rowe’s non-destructive method, an entire artifact goes into in a vacuum chamber with a plasma. The gas gently scrubs or oxidizes the surface of the object to produce carbon dioxide – CO2 – for the C-14 analysis, without damaging the artifact.

“We can energize the plasmas so that they are really hot, but we can also tune them down so they are extremely gentle,” Blinman said as Rowe and his crew fired up their machine to test the bison tooth and sheep bone.

He showed a picture of a turkey feather that had been tested and hardly looks ruffled. “The experience of the artifact is no different than your body temperature or, worst case, Phoenix on a summer day,” he said.

The plasmas in Rowe’s machine are generated with radio frequencies, rather than electricity, and work like a cleaning agent to scrub off the CO2.

“We have to use the ultra pure gases because any contamination from modern, atmospheric CO2 is going to screw up the data. So he has bled off high-purity oxygen into a reservoir that we will then tap as we generate plasmas,” Blinman said.

And what’s unique about “Marvin’s Machine” is that it has five chambers, so multiple samples can be tested at once. “That helps our efficiency somewhat,” Rowe said. “To my knowledge, nobody has gotten more than one plasma running at one time.”

The Archaeology Institute of America’s Archaeology magazine named Rowe’s non-destructive dating method one of the Top 10 discoveries of 2010. It noted that he has refined the method to work on objects coated in sticky hydrocarbons, such as the resins that cover Egyptian mummy gauze.

“Archaeologists, meanwhile, are hailing the discovery as one of the most important in decades, particularly for issues surrounding the repatriation of human remains from Native American burials, which modern tribes don’t want to see harmed,” said the magazine.

Marvin Rowe, left, and Jeffery Cox, both scientists at the New Mexico Office of Archaeological Studies, adjust the Low Energy Plasma Radiocarbon Sampling device they built at their lab in Santa Fe. (Eddie Moore/Albuquerque Journal)

Answers raise other questions

Fast forward a few months from Rowe’s demonstration for the Journal and the results are in. Blinman explains that, after the samples went through “Marvin’s Machine,” the results were sent to a lab in Zurich, Switzerland, for analysis.

“There are very few radiocarbon labs that will direct date carbon dioxide gas,” he said. “Other labs would turn it into graphite and that could add potential error to the system.”

The bottom line is that the bison tooth is most likely from between 530 and 685 AD, with 650 AD considered the mean average.

“It’s one of the earlier dates we have from that site,” said Akins, who now has most of the answers she needs to complete her report on the Coyote Canyon rock shelter. But it doesn’t answer all the questions.

What’s curious, she said, was that there’s bison tooth found there at all. The location is not a spot where buffalo would roam, so it was most likely brought there.

But why? If it were carried in as food supply, why weren’t there more buffalo bones found there? And why bring the head, from which little meat can be extracted?

“Ceremonialism is a pretty strong thing,” she said, purely speculating it could have been used for ceremonial purposes. She noted that deer heads have been found in kivas that date to later times.

And who brought it there in the first place?

“That’s a good question,” Akins said. “Back that early, we just don’t know.”

It could have been early Tewa people or nomadic groups coming in from the plains to escape the heat, she said, “but there’s no way of knowing. That early, we don’t put a label on it.”

The date returned on the sheep bone was a disappointment. It most likely is from the 1930s.

“What we were looking for there was something from the late 1800s or early 1900s,” she said.

The results suggest that people were still herding sheep in the area in the 1930s, “but sheep herders probably didn’t eat their own sheep,” she said.

“Marvin’s Machine” and the Low Energy Plasma Radiocarbon Sampling process doesn’t answer every question and sometimes raises more questions. But it can bring us closer to understanding our past.

“If you don’t really care about ordering history, you don’t care about dating,” Blinman said. “But if you want to order history, or you want to establish big-picture views about climate change and the extinction of Ice Age mammals and fauna, then this is one of the best tools we have available to us.”

Casey Nocket pleads guilty to vandalism

Via Full article / Casey Schreiner

Casey Nocket (aka Creepytings), who may be the most high-profile outdoor vandal in memory, pleaded guilty this week to seven misdemeanor charges of injury and depredation to government property.

According to the plea agreement, Nocket agreed that the government recommended she be sentenced to an initial term of 10 days imprisonment and 100 hours of community service, and that she was responsible for financial restitution which may be in excess of $1000. The plea bargain also stipulates that no portion of financial obligations can be discharged or nullified via bankruptcy.

As of June 13th, Nocket has so far been sentenced to:

- 24 months probation

- A ban from entering all lands administered by the National Park Service, National Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for the purpose of recreation during that 24 month probation

- Prepare a formal written apology to the National Park Service

- 200 hours of community service in the National Park Service or other public lands, with a strong preference for graffiti removal

The maximum sentence for depredation of government property is one year and $100,000 per count, along with one year of probation and a $25 fee per count, meaning Nocket could face 7 years incarceration, 7 years of probation, and $700,000.

The restitution hearing is currently scheduled for December 2, 2016, although the parties may agree on an amount before that court date.

+

Chain, Chest, Curse: Combating Book Theft in Medieval Times

Zutphen, “Librije” Chained Library (16th century) – Photo EK (more here)

Do you leave your e-reader or iPad on the table in Starbucks when you are called to pick up your cup of Joe? You’re probably not inclined to do this, because the object in question might be stolen. The medieval reader would nod his head approvingly, because book theft happened in his day too. In medieval times, however, the loss was much greater, given that the average price of a book – when purchased by an individual or community – was much higher. In fact, a more appropriate question would be whether you would leave the keys in the ignition of your car with the engine running when you enter Starbucks to order a coffee. Fortunately, the medieval reader had various strategies to combat book theft. Some of these appear a bit over the top to our modern eyes, while others seem not effective at all.

Chains

The least subtle but most effective way to keep your books safe…

View original post mais 1.207 palavras

Location, Location: GPS in the Medieval Library

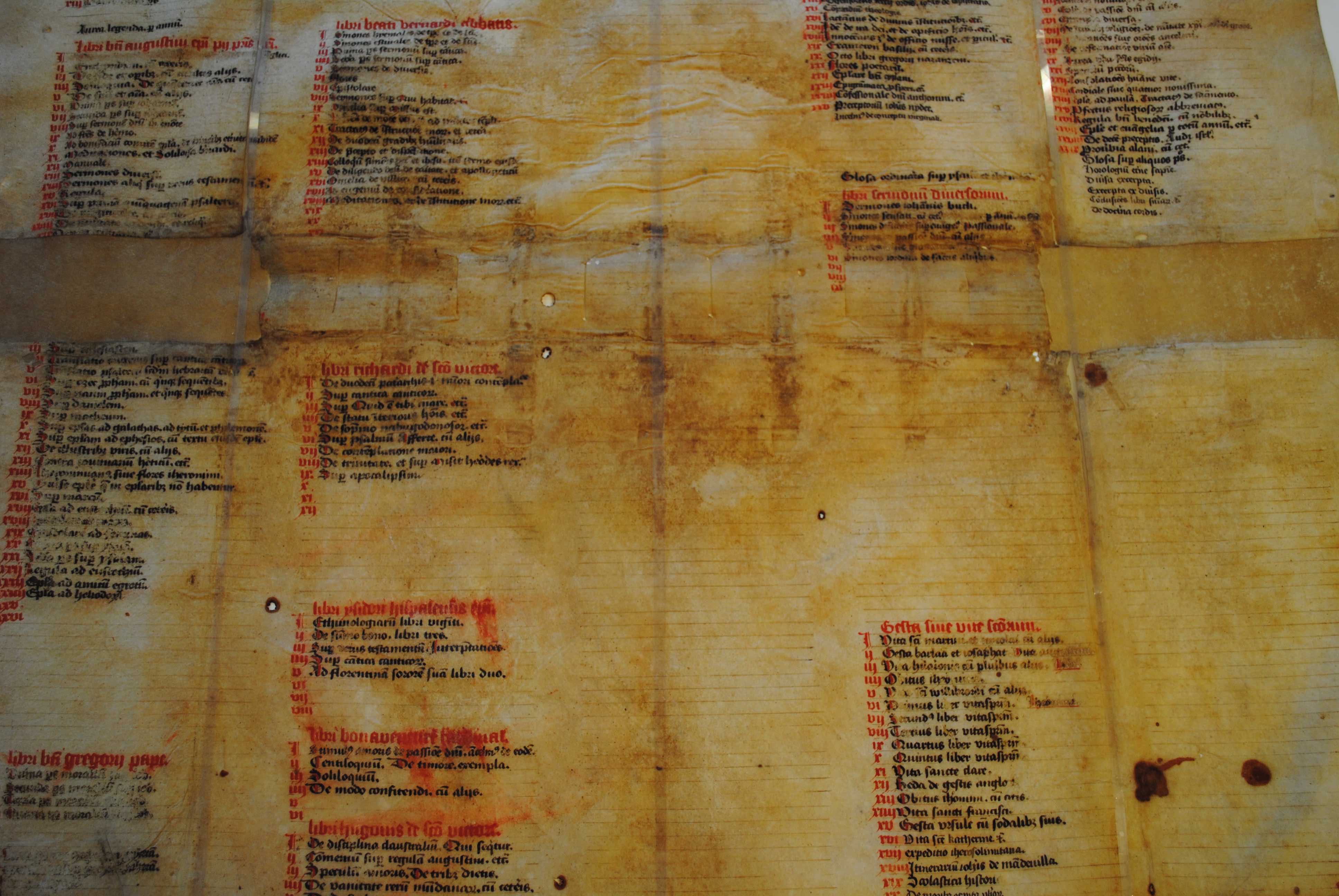

Leiden, Regionaal Archief, Kloosters 885 Inv. Nr. 208A (wall catalogue, 15th century) Source : https://www.flickr.com/photos/77326655@N04/7153179555

Books love to hide from us. While you were sure you put your current read on the kitchen table, it turns up next to your comfortable chair in the living room. As you handle more books at the same time, it becomes increasingly challenging to keep track of their location. In the Middle Ages it was even more difficult to locate a specific book. Unlike today, medieval books lacked a standard size, so you couldn’t really make neat piles – which sort of brings order to chaos. Finding a book was also made difficult by the fact that the spine title had not yet been invented.

So how did medieval readers locate books, especially when they owned a lot of them? The answer lies in a neat trick that resembles our modern GPS : a book was tagged with a unique identifier (a shelfmark) that was entered into a searchable database (a library catalogue), which could subsequently be consulted with a handheld device (a portable version of…

View original post mais 989 palavras

Medieval Apps

How about this for a truism: a book is a book, and something that is not a book is not a book. This post will knock your socks off if you are inclined to affirm this statement, because in medieval times a book could be so much more than that. As it turns out, tools were sometimes attached to manuscripts, such as a disk, dial or knob, or even a complete scientific instrument. Such ‘add-ons’ were usually mounted onto the page, extending the book’s primary function as an object that one reads, turning it into a piece of hardware.

Adding such tools was an invasive procedure that involved hacking into the wooden binding or cutting holes in pages. In spite of this, they were quite popular in the later Middle Ages, especially during the 15th century. This shows that they served a real purpose, adding value to the book’s contents: some clarified the text’s meaning, while others functioned as a…

View original post mais 767 palavras

Horseracing rules found on 2,000-year-old tablet in central Turkey

Source Full article / KONYA – Anadolu Agency

Horseracing rules written on a 2,000-year-old tablet were uncovered in the Beyşehir district of the Central Anatolian province of Konya on May 2.

The tablet, which is part of the Lukuyanus Monument, was apparently built to honor a jockey named Lukuyanus, who died at an early age in the Pisidia era.

Professor Hasan Bahar from Selçuk University’s History Department said the tablet was found at the site of an ancient hippodrome.

“This place was the site of a hippodrome. This tablet refers to a Roman jockey named Lukuyanus. From this tablet we can better understand that horse races and horse breeding were done in this area,” Bahar said, adding that the Hittites built such monuments for the surrounding mountains, which they believed were holy.

+

Embracing the Digital Future of Art Books

Source Full article / James Cuno

Getty Publications has inaugurated a new series of open-access collection catalogues available online, as downloadable ebooks, and in print.

Getty Publications has just launched two born-digital collection catalogues exploring groups of ancient objects in the Museum’s collection: Ancient Terracottas from South Italy and Sicily and Roman Mosaics. These two titles inaugurate a series of dynamic, user-friendly, technologically robust digital publications focusing on the Getty collections that complement our many distinguished print publications.

Terracottas and Mosaics

The Terracottas catalogue, by Italian scholar Maria Lucia Ferruzza, highlights sixty notable objects and includes an annotated reference by Museum curator Claire L. Lyons to the more than 1,000 other such works in the collection.

The Roman Mosaics catalogue documents the Museum’s complete collection of these works and is published in conjunction with the exhibition Roman Mosaics across the Empire, now on view at the Villa. Curator Alexis Belis organized the exhibition and wrote the catalogue, which also has contributions by other scholars.

Why Digital Catalogues?

Following the Getty Foundation’s successful Online Scholarly Catalogue Initiative(OSCI), more and more museums have been looking to digital formats for their collection catalogues. Digital formats allow for greater access, more flexibility, and interactive features not possible in print books.

+

These three Earth-like planets may be our best chance yet at detecting life

Source Full article / Rachel Feltman

Artist’s impression of the surface of one of the three planets orbiting an ultracool dwarf star just 40 light years from Earth. (ESO/M. Kornmesser)

It seems like scientists are finding potentially habitable planets all the time these days, and they are — the Kepler Space Telescope is very, very good at its job, even though it’s technically broken. But the three exoplanets described Monday in the journal Nature manage to stand apart: According to the scientists who discovered this trio, the Earth-like worlds might represent our best-ever shot at finding signs of alien life.

The three planets were detected based on the dimming of the star they orbit, which has been named TRAPPIST-1 for the telescope it was discovered with (TRAnsiting Planets and PlanetesImals Small Telescope). As the three planets orbit, transiting in front of TRAPPIST-1 from the telescope’s perspective, the star blinks and dims out of our view. Scientists use this dimming to calculate the size of the planets and their distance from their host star. Because planet composition is closely tied to these metrics, scientists can say with confidence whether a world is rocky, like Earth — as opposed to a massive planet composed of gas or ice — and whether it could host liquid water.

[NASA estimates 1 billion ‘Earths’ in our galaxy alone]

The three worlds are close by, located just 40 light years away in the constellation Aquarius — the water bearer. But the fact that they’re Earth-like and promising doesn’t mean these planets actually hold water.

+

10 of the best European cities for art nouveau

Source Full article / Jon Bryant

Museu Arte Nova Casa do Major Pessoa Aveiro By amaianos from Galicia [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

Over the last 100 years the demolition of art nouveau structures has been ruthless. French architect Hector Guimard’s innovative Parisian concert hall was pulled down as early as 1905 and only three of his roofed entrances to the Paris metro remain. While Barcelona, Vienna, Munich and Subotica claim stunning yet isolated art nouveau buildings, other cities have managed to preserve the style as part of their dominant architectural heritage.

Aveiro, Portugal

Halfway between Porto and Coimbra, Aveiro is a floating city full of art nouveau treasures. Aveiro’s economy still comes from seaweed, salt and ceramics, and it was the revenue from these, plus the wealth of returning emigrants who had grown rich in Brazil at the end of the 19th century, that led to requests for extravagant new residences. Take a tour on one of the gondola-style moliceiros to the Rossio district; try the local ovos moles delicacies in one of the bars where Aveiro’s particular style of arte nova includes pale-shaded tiles, ironwork balconies and floral mouldings. The Museu de Arte Nova is in the Casa Major Pessoa on Rua Dr Barbosa Magalhães and its first-floor tearoom, the Casa de Chá, turns into a cocktail lounge serving caipirinhas in the evening – its floral designs and tiled birdlife motifs masked by mood lighting after dark.